David Slack: In a time of broken supply chains—doing it for ourselves

In the space of just a month or two, old certainties and assumptions have been turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic. What are the impacts? What comes next?

In this series, Auckland-based columnist, author, and speechwriter David Slack deep-dives into the New Zealand economy—sharing stories from the past, and exploring possibilities for the future.

In part 1 of the series, David examines NZ’s history of economic self-sufficiency.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the big questions has been: how will this just-in-time 21st century economy cope? What will happen to global supply lines, impaired by closed borders and fractured economies?

News headlines make the drumbeat: Pharmac reveals hair-raising medicine supply chain complications and From farm-to-table: Is the food supply chain breaking? For manufacturers, for distributors, for consumers, it feels increasingly as though we could be in for shortages, outages, and long waits.

It's not just the supply lines in question; it’s also the suppliers. There is real uncertainty about the health of the world's largest economies. One in eight workers in the United States have lost their jobs since the epidemic began. It is a nation in turmoil. That in turn puts export prospects for China at risk, and lifts the likelihood of ripple effects all around the world, with holes in supplies, and deliveries that just don't arrive.

Is there a lesson for us here? Have we made ourselves too reliant on an interconnected world? Could we do with a greater degree of self-sufficiency?

Innovation born out of isolation

While this turmoil persists, we find ourselves talking about doing things the way we did once before, drawing on a rich history of innovation born out of isolation, and honed on every back country farm. When you can’t get it from far away, you make it yourself.

There is a notion held by some New Zealanders, perhaps many of them, that “we can't do manufacturing”. That’s possibly an echo of the received wisdom of the economic reforms of the 1980s: that we could never match the efficiency of factories in Asia, and that the lengths we’d gone to to protect local industry and local jobs (like assembly lines putting back together cars that had been taken apart in Japan) was all a bit comical.

But that would be a misgiven opinion. Local manufacturers can be exceptionally good at short-run manufacturing, and taking a request for any kind of product and turning it into a physical reality. It's true to say they would struggle to match the delivery speed and price of Chinese factories operating on a huge scale. But when priorities change, the calculation changes too. This pandemic has surely shown us that certain goods and services matter too much to ever be unobtainable: pharmaceuticals, protective equipment, and ventilators, to name a few.

Given the capability of our manufacturer to take up the challenge, and given the uncertainty of supply of so many essential products, the argument for expanding local manufacturing and doing some import substitution begins to look pretty attractive.

The role of government

We’ve done it before. The strategy the government followed in the post-war years before we embraced a purely open and free global market gives us a starting point to follow: fostering manufacturing of a wider range of goods and products, using import licences and tariffs to give local manufacturers a leg up and protection from competition, in the name of insulating the country from further economic harm. In a world where assurance of supply becomes more strategically significant, the calculation must surely be remade about the role of local manufacturing and the Government’s role as its enabler.

This time around would not need to be a fortress economy strategy, so much as one that ensured a range of important goods were produced here on a basis of enough support and protection to make a manufacturer viable. There are some items we would likely never seek to substitute—the iPads and the CAT scan machines, for example, are things we could continue to send our dollars out into the world for. But for certain strategically important goods and services, we could turn the emphasis towards the local, and give manufacturers the support they needed to make it work.

These uncertain times give the Government licence for boldness in investment, and in shifting policy settings, to carry us through extreme economic turbulence. The role it might take in helping local manufacturing to expand could take a variety of forms: equity investor, underwriter, facilitator of seed capital. The crucial point would be to ensure that as much as possible, the headwinds that can impede an operation as it starts out are removed.

Ideally, it would approach the project with the aim of achieving viability and growth and perhaps even export capability. It might also evolve that strategy in concert with Australia, which has mooted revival of domestic manufacturing.

Manufacturing and tech

There is plenty of established capability to build from. In Canterbury, enterprises like Tait and PDL have an accomplished history of success in high-tech manufacturing. There is also a broader tech ecosystem to be tapped into across the country, in towns like Napier, Gisborne, Queenstown and Nelson, innovation hubs like Dunedin all embracing the 21st century ethos of “get a few of the right people and off you go”, and an enduring strength of New Zealand enterprise—the small multidisciplinary team. If you’re small, you manage to do things that bigger organisations in larger and older nations cannot. That's reflected in a strong trend here of incubators and collegial spaces and startups.

That nexus of manufacturing and tech is critical. In the first wave of manufacturing in New Zealand, the significant input was the assembly line labour force. Modern manufacturing pivots much more around the application of advanced technology. Increasingly, those two elements are blending together, and the capability here in tech is impressive and exciting. Tech exports are worth $9 billion per annum and showing 11% growth each year, and New Zealand has acquired a reputation amongst tech investors as second only to Israel in terms of its innovation.

That suggests a strong capability to broaden out the economy and create new jobs, not just directly in tech and manufacturing, but everything that builds up around it.

Diversification and escaping narrow confines are not at all a new question for the New Zealand economy, but the importance of it is in sharp focus in this crisis. And notwithstanding the extremes of unhappy possibility this pandemic has created, New Zealand may right now be at a point of great promise.

Just as in the Bronze Age where your prosperity was determined by the capacity to smelt bronze, so in our time it has been the need for oil. But no more. As oil declines, New Zealand has renewable energy, one great massive battery, in terms of lakes, wind, maybe tides. As the cost of energy storage plunges, we find ourselves with an abundance of renewable power we can store and use for all our needs: productions, infrastructure, home and hearth.

And that's just one part of a very favourable arrangement. We also have abundant food, and we have access to technology. Our prospects get very exciting when those elements are brought together to their fullest potential. Clean technology responses to climate change problems, for example, offer vast possibilities, and there is already exciting work of that kind happening here.

We might not ever realistically contemplate entire self-sufficiency in the short or medium term, but for the present, it's clearly desirable for us to acquire a greater degree than we currently have. For the long term, though, that broadening and expansion could set us up for large changes, and perhaps a great deal more self-sufficiency and sustainability, in a world of Artificial Intelligence and robotics and automation and 3D printing.

Ok, now for the legal bit

Investing involves risk. You aren’t guaranteed to make money, and you might lose the money you start with. We don’t provide personalised advice or recommendations. Any information we provide is general only and current at the time written. You should consider seeking independent legal, financial, taxation or other advice when considering whether an investment is appropriate for your objectives, financial situation or needs.

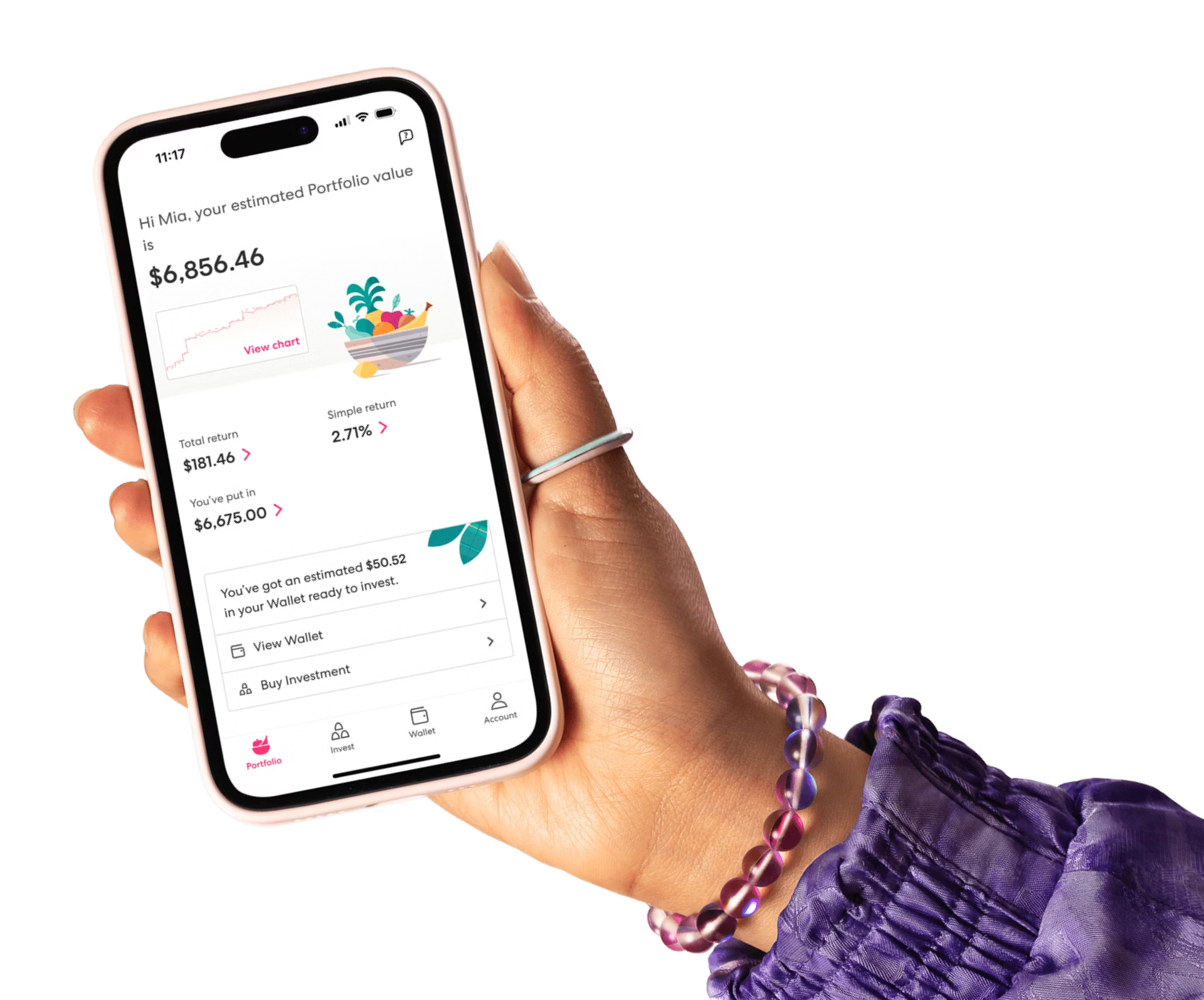

Join over 800,000 investors